In many ways, Cuyahoga County politics and many of its players haven’t changed since I’d left the area in 1999. It was interesting to return in 2020 as many younger people were beginning to run for office with an eye on challenging the Democratic machine politics that govern the metro area, which haven’t benefited most of the region’s poor and working-class people.

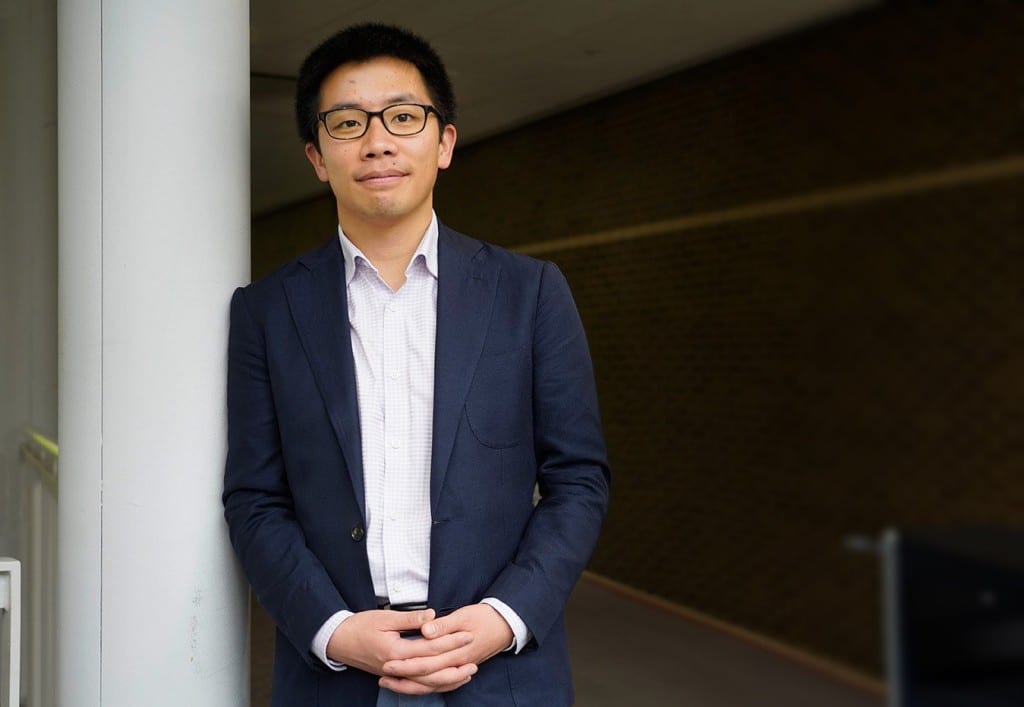

So when Matthew Ahn announced his run for Cuyahoga County Prosecutor, I thought it was interesting. But I was completely shocked when he successfully advocated for his vision for the office, such that it blocked the local Democratic party from endorsing incumbent Michael O’Malley in the primary. (The party’s endorsement was “no endorsement.”) Primary election day will take place on March 19.

Ahn, in his early 30s, Asian American and bisexual, may not fit the image of whom we normally see succeed in local politics. But he seems to be shaking things up in this race that have less to do with his identities, and more because he is tapping into the various frustrations communities have about getting to the root causes of violence and crimes of poverty.

I spoke to Ahn about his vision for the office and dealing with crime in the region, his view on our county’s use of criminal statutes targeting people living with HIV and his identities’ impact on his run.

Kenyon Farrow: So let’s begin with your career as a public defender. You had an interesting start in music composition and being on “Jeopardy!,” but what were the things in the criminal justice system in Cuyahoga County that made you want to run for Cuyahoga County prosecutor, having been a public defender?

Matthew Ahn: I think there were really four major issues that I really found unacceptable. Number one, over the last five years Cuyahoga County has tried nearly as many children as adults, as many as the rest of Ohio combined. Ninety-two percent of those children are Black. This is something that started basically right when my opponent took office. The trend in the early to mid-2010s was fewer children being tried as adults, and then all of a sudden between 2016 and 2018, the rate doubled. And children who are tried as adults are much more likely to commit another crime upon their release than children kept in the juvenile court system, even when you control for the same charges. It is not making us more safe.

Number two, over that same period of time, Cuyahoga County has issued more death sentences than any other county in the United States. Not just Ohio, but the entire country. And moral questions aside, the death penalty is a policy failure on every level – it does not reduce the murder rates and it is prone to error. We’ve seen eight wrongful death sentences [during O’Malley’s time in office] in Cuyahoga County alone. It’s prone to bias and it’s actually more expensive than sentencing somebody to life in prison without parole.

The other thing is that because of the length of time that the appeals take, it means that the families of victims actually sort of have to relive a lot of that trauma over and over and over again, in ways that they wouldn’t if we were seeking life without parole.

So number three is about pretrial detention. The county government here is talking about building a $2 billion jail in Garfield Heights. Part of the reason that proposal is so expensive is because there are more people being held pretrial than necessary right now, we’re still using a cash bail system and it doesn’t have anything to do with public safety. In our county jail now, there are people who cannot afford a cash bail amount of less than $1,000. Meanwhile, at the other end, people who are charged with very serious crimes (up to and including aggravated murder) are still getting a bond amount and thus a chance to pay their way out of jail while the case is pending. And so at both ends, it doesn’t make sense.

If we switched to a public-safety-based sort of system for determining whether somebody should be in jail or not – if either you’re a threat to the community or flight risk, you should be in jail. Or if you’re not, then you should be released pending whatever conditions we think will assure the safety of community. The jail population would then decrease and our public safety would improve. And, you know, the county would probably save hundreds of millions of dollars on a new jail proposal.

Finally, we’ve seen a lot of convictions overturned over the last several years because oftentimes the prosecutor’s office here years and decades ago didn’t turn over some evidence, and some of these folks are getting out of prison after 20 or 30 or 45 years because of this new evidence in their defense. And our county prosecutor’s office, in many of those cases, has chosen to take those folks back to trial on their original decades-old charges. That’s a waste of public resources, a waste of everybody’s time. Every single one of these people have gotten acquitted on every trial. And it just is this sort of approach that seems to assume that no wrongful conviction has ever happened in Cuyahoga County, despite the history that we have. Cuyahoga County actually leads Ohio by a wide margin in confirmed wrongful convictions. This is part of the approach that I think led members of the conviction integrity units, which is supposed to be tasked with reviewing some of these wrongful conviction claims, to all resign together in 2022. Nobody has been appointed to replace them. So those are, those are sort of the big, the big issues that I think can be addressed fairly quickly by a new prosecutor.

Since I moved back to Cleveland in 2020, I’ve been struck by how many people that I’ve met, particularly a lot of young Black gay men, who are completely astounded that I would move back there after living in a lot of the cities they’re trying to get to like D.C., New York or Atlanta. I would argue that the population drain is partially due to a lack of jobs and opportunities. But also the disillusionment I think a lot of younger Black queer folks in the city have is connected to some of the criminal justice issues, and overall the lack of feeling seen, safe and cared for by city and county leadership. What have you seen in the way the criminal justice system here impacts just how people live, and who is often subjected to it in different respects?

I think the criminal justice system here really does shape people’s lived experience in the city really deeply in a lot of different ways. And that’s both from the perspective of victimization, and criminalization. I think what we’ve seen over the last couple of decades is a very reactive approach. And it doesn’t address the root problems that a lot of folks are dealing with, especially in marginalized disinvested communities. What we see the prosecutor’s office doing is simply trying to arrest their way out of the issue.

And that’s true across a wide range of topics. That includes, right, things like drug crimes, things like violent crimes, but it also includes a handful of crimes that we know single out people living with HIV as the sort of class that will receive additional punishment. There are I believe six crimes in the Ohio Revised Code, where if you are a person living with HIV, your penalties are substantially higher for the exact same crime than for anybody else. Things like solicitation, which is a third-degree misdemeanor typically, but it is a third-degree felony if you are a person living with HIV. And Cuyahoga County has actually been the leader in the state by a wide margin in these kinds of prosecutions, even though it’s not actually backed up by the data science. More than a quarter of these prosecutions across the state from 2014 to 2020 came from Cuyahoga County. Even though we know these prosecutions go against the science, like with U=U [people living with HIV who are on treatment and become “undetectable” are also unable to transmit the virus to others or are “untransmittable”].

And so these kinds of cases make it difficult for folks to feel not only just welcome but that they can even talk about some of these issues, even with their friends or with their social circles. It has this really damaging, chilling effect in terms of just even being able to have open conversations about the kinds of things that folks are going through and being able to connect those with help or services that they may need.

You are queer. And you haven’t run with that as the foreground of your campaign. So if you can. talk a little bit about that decision, and how you feel like that may impact your campaign.

I am a bisexual person in a straight-passing relationship. It is often very tricky for bi individuals in particular, who I think struggle with where they fit in the LGBTQ+ constellation.

I don’t know if folks are more willing to vote for me because I’m queer, sure, but I want to actually have a conversation about the issues. I believe that what qualifies me to be county prosecutor is not the fact that I’m bi. It is the fact that I have thought about these policies and the ways in which the office can be structured. And yes, my experience as a bi person informs the ways in which I think the structure needs to be set up for fairness for everybody, but it’s not on its own a qualification. It is more about how I use my identity to understand the ways in which the system can sort of be disproportionately enforced against people like me. And I think that that is far more important than whatever demographic boxes I may happen to check. It’s not that being Asian qualifies me to be prosecutor. But my particularly unique experience has helped me to think hard about how best to set the system up for everybody, not just for those who can afford the best representation.

So fast forward and let’s say you get elected, and let’s see your first term at its end, four years from now. What does success look like at the end of your first term?

I hope that what I will have accomplished by then is reversing some of the issues that we’ve talked about already, I think it’s just really to have rebuilt the office to be one that runs on data, that runs on research and that runs on getting things right—not necessarily looking to beat the other side but we’re actually trying to do what is best for the victim and for the community. And I want that to be the overarching culture of the office moving forward. And if we can do that, then I think that we’ve succeeded, and that Cuyahoga County can improve not just on criminal justice outcomes, but also in other societal social markers. We can’t solve the criminal justice issues in a silo. It’s going to take us thinking bigger about what our communities need. And if we can get folks on board with that big-picture thinking, we can make an impact on far more than just the criminal justice system. 🔥

IGNITE ACTION

- To learn more about Matthew Ahn, visit him on his website, Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

- To register to vote or to check your voter eligibility status in the state of Ohio, click here.

Know an LGBTQ+ Ohio story we should cover? TELL US!

Submit a story!