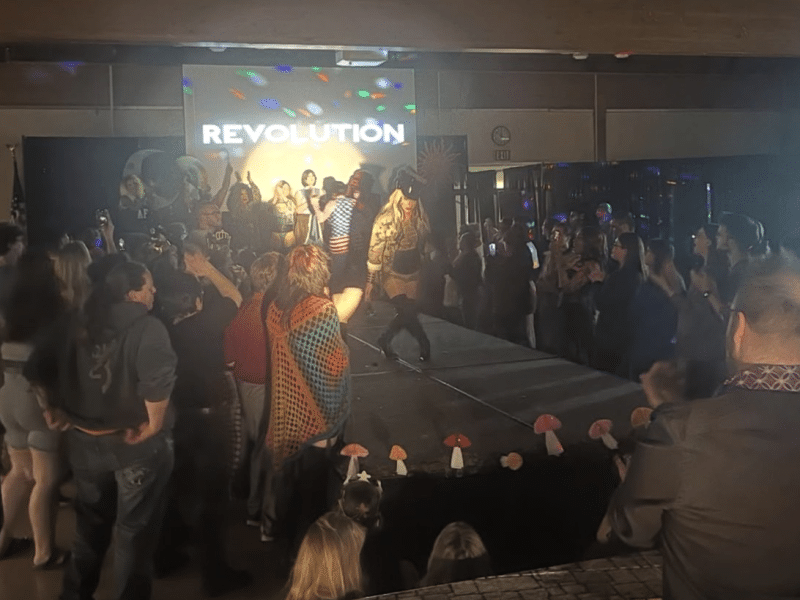

Almost 9,000 feet above sea level sits a small mining town in Colorado with no stoplights. Creede is home to an award-winning theater with diverse casts that presents challenging plays like – The Royale and Native Gardens – to a predominantly white conservative population.

Director Kahane Corn Cooperman was fascinated by this little mining town and made it the subject of her feature-length documentary “Creede U.S.A.,” set to show at the Cleveland International Film Festival on Saturday, March 29, and Sunday, March 30. Both screenings will have a Q&A with Cooperman and one of the participants from the documentary.

“Theater in general can be transformative for people,” Cooperman said. “It can be a sanctuary for people. It can open your mind. It can show you what other people’s life experiences are, and Creede does all that.”

The documentary follows people of all politics as they navigate intense discussions around LGBTQ+ issues and school safety, but still find a place to come together as neighbors – often in the Creede Repertory Theater. Every summer, new cast and crew come to the theater to perform. Often, they are BIPOC and part of the LGBTQ+ community. The film doesn’t use narration. Instead, the movie takes on a more observational role with Creede and uses interviews to expand on the town’s history and conflicts.

Lexy Mead is a notable character in the movie, as Lexy and their best friend, Waverly Pearson, joke how they might be the first nonbinary teenager in Creede. The film highlights Lexy’s supportive family and how they did their research to understand Lexy’s queer identity and advocate for them.

The last half of “Creede U.S.A.” focuses on the school board of directors’ conversations surrounding a new health curriculum. Board members argue about how to discuss gender identity and sexuality in the classroom, which could not only impact Lexy but future children exploring those sides of themselves.

Cooperman was living in New York City when she first happened upon Creede in a New York Times article. She recalled thinking it was about time that she stepped outside of her bubble.

“I was feeling a little itchy and uncomfortable in my own skin,” she said in an interview with The Buckeye Flame. “What I found was not only a fascinating story in and of itself, the history of this town and the history of the theater and how they are integrated, but also how people engaged with each other for the survival of their community.”

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

THE BUCKEYE FLAME: I was super drawn into the film. I’ve been in rural places where people living there are not like what people in a city bubble might think.

COOPERMAN: You can’t not judge a book by its cover, as cliche as that sounds, but like everyone is more nuanced than you think. And I feel like all the subjects who appear in this film surprise you one way or another based on either how they look or something they say, or a flag that’s outside their establishment or whatever.

[The film] shows the polarization, but on a scalable level that doesn’t feel so unbelievably overwhelming. But beyond that, you get to see how they negotiate it.

Was there a moment in production where you felt everything clicked?

My first few trips there were just completely by myself. They were my first trips out of COVID. I had been wearing a mask outdoors, outside of my home for, you know, a year or whatever. I was suddenly going to this place that you had to fly to Denver and then drive five hours.

I couldn’t be more of an outsider. When there’s someone new in town, these people know it.

What I was learning is that Creede itself has an incredible history. We couldn’t include all of it in the film, but it’s an amazing pure, true American West kind of history. Then the fact that this theater company comes in as an invitation of the town – this amazing thought that the very thing that brought in new ideas and outsiders was brought in by the town.

The people in this town, 97% white town, more conservative than not, have this constant exposure to other types of people. Some embrace it. Some don’t love it. It’s a really interesting thing.

I had this fascinating world of the theater, but I knew that in the Venn diagram of that story, it was gonna be in the middle where the ideas that they represented kind of came together. I didn’t quite know where that was gonna be.

Maybe six months into filming, I learned about some of the things that were going on at the [school’s board of directors] because one of the subjects that we follow both works for the theater and was an elected member of the board of directors and was the [board’s] only progressive voice, which I thought was interesting.

That’s when it clicked because suddenly I had a way to show how all of these opinions and voices and people you were meeting come together into a nondescript room. And to have really some of the toughest conversations in this case around guns and around LGBTQ+ issues that our whole country is facing, but not everyone is discussing.

They are discussing it face-to-face on a human level.

How do you think the message of “Creede U.S.A” is landing in the context of the last few months?

We knew the film was coming out – [it] just premiered [on March 9] at South by Southwest (SXSW). Things are a little different than when we started. So how do we think about that?

We don’t ever want anyone to think we have the answer: You just talk to people and everything’s fine. That can’t be the case. But I do think that it’s a step. I do think getting out of your comfort zone is a must. I do think engaging with people who aren’t like you, and – honestly, I can’t be addressing the far extremes on either side – but for the people in the middle, having conversations like that is very worthy. Talking to each other should not be a novelty, but it is right now.

It’s about not making assumptions about people and engaging across differences, and hopefully it’s shown through this film with a human and respectful approach.

Ohio is having a lot of young LGBTQ+ people find ways to get out. Lexy, growing up in a conservative town, wants to stay. How does Creede retain people?

I think it’s all about balance. In Creede, community rises above everything. Lexy, whose parents are incredible, has found support and welcome from the theater company, but also from community members all around Creede more than they have been subjected to hate. And I think that love for community and belief in the community and the feeling of support ultimately [prevails], even knowing there’s people that don’t believe that Lexy is who they are.

[Lexy’s best friend] Waverly comes from a very conservative family – and, by the way, when I say “conservative and progressive,” it’s not that simple – and I love the fact that both of them feel strongly like “I’m going to college and I’m coming back.”

I feel like ending on the potential, planting a seed for the future. Creede is still going to have these different kinds of people and everyone has to figure it out.

What’s theatre to Creede?

It’s definitely different things to different people there.

One [has to do with] who comes to town to [work with the] theater every summer. You add the cumulative effect of that since 1966. It’s like a social experiment. When the summer’s over, it’s like every summer Creede kind of goes back to its normal self and its normal patterns, but they know this is gonna happen every year.

Just by osmosis it’s exposed. People who would not have normally been exposed to all different kinds of people from all different places, people of color, people from the LGBTQ+ spectrum, people from cities, people from all over the place. They wouldn’t necessarily even be seeing those kinds of people, let alone engaging with them at the gas station or at the store.

That presence is because the theater’s there.

There’s also the plays themselves. The theater is very intentional about the plays that they pick and choose. Of course, they understand and embrace who their audience is and want to please them, but they also work to pick plays that touch on important topics and subjects that aren’t necessarily forefront in the minds of people.

Someone says it in the film, but theater – it is like a bit of an empathy machine. You do get to see life in another person’s shoes, and it’s good theater.

Just because they’re a miner or a rancher, it doesn’t mean they’re not a creative person, too. And just because you’re a theater person doesn’t mean you’re not a gun owner. It’s all mixed, and I think that’s the beauty of this place.

Theater in general can be transformative for people. It can be a sanctuary for people. It can open your mind. It can show you what other people’s life experiences are, and Creede does all that.

And to have that in a town of 300 people, that’s pretty awesome. 🔥

IGNITE ACTION

- Tickets are available on Cleveland International Film Festival’s website.

Know an LGBTQ+ Ohio story we should cover? TELL US!

Submit a story!